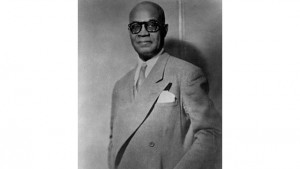

ROBERT DOUGLAS 1881-1979

Robert Douglas was born in St. Kitts on the 4th November 1881. The 1880’s saw a dramatic decline in the sugar industry. By the 1890’s St. Kitts was experiencing serious social and economic difficulties that culminated in violent disturbances in 1896. For many migration in search of work was the only option. Douglas was among the many Kittitians who made the move.

Douglas arrive in Harlem, New York in found work as a doorman. During one of his days off he was invited by a fellow doorman to see a basket ball game. Basket ball was new to him but he enjoyed it enough to organise two amateur teams, the Spartan Braves and the Spartan Hornets both of which played other New York City clubs. Soon he quit his doorman’s job and started a Caribbean Athletic club promoting various sports but with a particular emphasis on cricket, a game he would have enjoyed in his home in the West Indies.

It was difficult at the time for black persons to become professional sports men. Discrimination barred them from participation in major teams and professional leagues. The only way out of this situation was for black people to organise their own sports clubs. In 1923, he launched the first black professional basketball team.

That year he approached, William Roche, the owner of the Harlem Renaissance Casino. The first floor of the building was a movie theatre and the second floor was a ballroom. Douglas wanted to rent the ballroom for basketball games. At first Roche was worried that that kind of activity would ruin his beautifully polished dance floor but when Douglas offered to name his team the Renaissance he saw a chance of some serious publicity and agreed to the allow the team to play.

Douglas arranged for his team play with the dance bands. This meant that patrons enjoyed several hours of dancing and a basketball game in the same night. Portable baskets where installed in front of the bandstand and folding chairs along the sidelines and on the 30th November 1923, the Harlem Renaissance met their first challengers the Chicago Collegians whom they beat with a score of 28 to 22. The Rens became a “fancy passing team that moved the ball around with such wizardry and deception that the opposition sometimes seemed helpless and beleaguered.”

After their first season, Douglas and the Rens travelled by bus across the US maintaining a hectic schedule of a game a day and twice on Sunday, often playing more than 120 games annually. They took on all comers – professional, semi-pro and black college. Their games against the Original Celtics were crowd pullers often drawing as many as 15 000 spectators. Civil on the court, the games between the two teams were often accompanied by race riots. Douglas and his team stirred away for trouble as much as they possibly could.

Despite the competition, a friendship developed between Douglas and Joe Lapchick of the Celtics. However, racism in the game and in the US generally was so rampant that Douglas often turned down invitations to join his friend at clubs and restaurants. He did not want to face the “stares of racist white men.”

But Douglas and his team often had to put up with more than just stares. They would not accept food or lodging while on the road. Instead they would drive the 200 mile journey to a game, drive back to sleep in places like Chicago or Indianapolis and then set out again the next day on a similar trek. Alternatively they slept on their team bus and ate cold sandwiches when they could not find safe accommodation. Throughout the whole ordeal, the coach’s tenacity kept the team focused on the game.

Douglas and the Rens did their talking from the ball court. In 1932 they won a 88 straight games in one remarkable 86 day stretch. Between 1932 and 1936, the team had a record of 473 to 49 games. In March 1939 they defeated the National Basketball League champions, Oshkosh All-Stars 34-25 and captured the championship at the first World Professional Tournament in Chicago. The Evening Telegram raved, “They are the champions of Professional basketball, it is time we dropped the “colored” champions title.”

During the World War II, travel restrictions put an end to the hectic routine that the Rens had engaged in. Douglas suspended play for the duration and then tried to regroup when the war was over. By then many of his players had moved elsewhere. When the American Basketball League was formed he managed to get the team included in 1948. As part of the agreement that allowed this move, Douglas had to move his team to Dayton, Ohio where they foundered and finally played their last game in 1949.

Douglas’ pioneering venture earned him the title of Father of Black Professional Basketball. His influence and the impact of his team continued to be felt in the years following its disbandment. His friend, Joe Lapchick eventually became the coach of the New York Knicks and was responsible for signing the first African-American to an NBA contract. His team’s remarkable performance of 2318 wins to 381 losses finally received the recognition it deserved in 1963 when the New York Renaissance was enshrined in the Basket Ball Hall of Fame. In 1972 Douglas became the first black man to be inducted into the Hall of Fame. Robert Douglas died on the 16th July 1979.