They arrived in droves starting at 5:30 a.m., desperate to secure a steady pay cheque. By midmorning, the anxious mob totalled 5,000 people.

They arrived in droves starting at 5:30 a.m., desperate to secure a steady pay cheque. By midmorning, the anxious mob totalled 5,000 people.

Sandals, a Caribbean hotel chain, was hosting a job fair in Barbados to hire staff for a brand new resort. Because thousands of people showed up for 600 jobs on the October morning last year, scores of applicants were forced to wait outside under the blistering sun. Things went from testy to unruly as the temperature neared 32 degrees; Sandals had no choice but to call the cops.

The chaos is one face of the ugly downturn sweeping through the Caribbean. Though the global financial crisis technically ended a few years ago, its punishing aftershocks are still being felt—and they’re amplified on island states that depend on tourist dollars for support. Countries like the Bahamas and Barbados are marketed as idyllic vacation spots with white sand beaches, but their local economies are anything but serene.

In the Bahamas, the unemployment rate was 15.7% at the start of February—higher than in Portugal, one of Europe’s worst-hit economies, and well over double Canada’s rate. The situation is even worse in Barbados—and arguably even more surprising, since the loyalty of British tourists to “Little England” had seemed to be bred in the bone.

The colonial tie meant little during the financial crisis, and the resulting downturn drove Barbados’s debt load to nearly 100% of its gross domestic product. Struggling to pay the bills, the government fired 3,000 public servants last year. It’s also gone cap in hand to hotel developers, offering major tax concessions to spur investment—hence the scene at Sandals.

Financial institutions are, of course, at the epicentre of this storm. Take the case of Sagicor Financial Corp., a leading regional life insurer, based in Barbados. Because the country’s sovereign debt has been downgraded several times, Sagicor’s corporate debt rating has also suffered. In January, the company abruptly announced it was relocating its head office outside of Barbados, shocking the island’s 290,000 citizens.

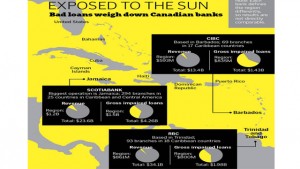

Canadian lenders have it even worse. Our banks are often praised for sidestepping the U.S. mortgage crisis and for avoiding the ugly economic woes that still wreak havoc in Europe, but the truth is, they’ve hit trouble in paradise. Royal Bank of Canada, Bank of Nova Scotia and Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce are by far the Caribbean’s three largest lenders, dominating both personal and commercial banking. Combined, they’ve written off more than $1 billion in the region since the Great Recession.

To stanch the bleeding, the banks have been restructuring their regional operations by shrinking their footprints and by leaning on specific countries, such as energy-rich Trinidad and Tobago, to drive growth. At first it seemed like a smart plan, but then energy prices plummeted. Some 45% of Trinidad’s GDP comes from the energy industry, as do 80% of its exports.

Shareholders barely noticed when Canada’s banks started suffering from this tropical malaise five years ago. Because the Big Six lenders were on a tear, many of their mistakes were glossed over. Bank CEOs, however, have warned that the bull run is waning. Spooked by spiralling writeoffs, investors repeatedly asked bank chiefs about the region at a major industry conference in January. More than anything, they simply want to know what the hell is happening in the backyard of Canadian banking.

A long history in the Caribbean

Canada’s commercial ties to the Caribbean run deep. Starting in 1864, the group that founded Merchant’s Bank in Halifax financed trade with British-owned islands in the Antilles. Ships leaving Canada packed with timber and flour returned home with sugar, rum and cotton.

Scotiabank planted roots in the British West Indies, as they were then known, by opening a branch in Jamaica in 1889. RBC began its Caribbean foray even earlier, in 1882, and CIBC set up shop in Barbados and Jamaica in 1920. Canadians were so enamoured with the region that Prime Minister Robert Borden talked to his British counterpart, David Lloyd George, about taking over some islands in 1919 (or so legend has it).

For all that history, our banks are sometimes still chided for being from afar. “Everybody always talks about these ‘foreign banks,’” says Anya Schnoor, a Jamaican who runs Scotiabank Trinidad. “I always say to everybody: If you’ve been in a region 125 years, we’ve kind of gone beyond” that line of reasoning.

The Canadian banks used to face tough competition from the likes of Barclays and Citibank, but that started to change at the turn of the century. In 2001, CIBC combined its regional operations with Barclays’ to form FirstCaribbean International Bank; five years later, CIBC bought out Barclays’ remaining stake for just over $1 billion (U.S.). It was the largest deal of CEO Gerry McCaughey’s era.

While Scotiabank largely opted for organic growth, investing in its local wealth and insurance arms, RBC inked its own acquisition in 2007, buying back Trinidad’s RBTT Financial Group for $2.2 billion (U.S.). (RBC originally owned RBTT, but sold it to public shareholders in the late ’80s.)

Each of these investments seemed promising at the time. With tourism booming and energy prices soaring, economic growth was robust—between 2000 and 2007, Trinidad and Tobago’s averaged slightly over 8% annually. The region’s profit margins were also fat, particularly in lending.

By 2008, the three Canadian banks had $42 billion in assets across the English Caribbean—2.5% of their combined total assets, but more than four times those held by the 40-odd locally owned banks. With such a dominant footprint, RBC, Scotiabank and CIBC hardly had to spend to build brand awareness—they could milk money just by being there. In 2007 CIBC FirstCaribbean made $256 million (U.S.), contributing 7% of the bank’s total profit.

Then the financial crisis hit.

At first, the pain wasn’t too severe because Brits, Canadians and Americans didn’t cancel the vacations they had booked before the crash. But in 2010, Jamaica became the first to blink, turning to the International Monetary Fund for assistance. Almost four years later, Barbados did the same when its central bank nearly ran out of its precious foreign exchange reserves. The government is now in regular talks with the IMF, which recommends sweeping changes. This suggests that two of the region’s three traditional economic powerhouses can’t support themselves.

Scotiabank was the first financial institution to acknowledge the pain. As the lead lender to a developer that bought resorts on Cable Beach in the Bahamas, the bank suffered a $75-million hit on its $200-million loan in 2010. Through a complex restructuring, a Chinese bank stepped in to bail out the developer, ultimately financing a project comprising six hotels, a 100,000-square-foot casino, 200,000 square feet of convention facilities and an 18-hole golf course. A year later, CIBC wrote down its investment in FirstCaribbean by $203 million.

It was then largely quiet until January, 2014, when RBC shocked its peers with plans to sell its Jamaican operations to Sagicor, incurring a $100-million loss. The year since has been chock full of charges and pullbacks, including another $420-million writedown of FirstCaribbean’s goodwill; the closing of RBC’s Caribbean wealth management business; and scores of loan-loss provisions from all three lenders.

Today, more than half of CIBC’s total gross impaired loans—or loans that show any signs of trouble—originate in the Caribbean. At Scotiabank, the equivalent share is 35%. In other words, this tiny cluster of islands has the potential to generate bigger writeoffs than both banks’ monstrous Canadian lending portfolios. As for RBC, 11% of its Caribbean lending portfolio is impaired, versus just 0.33% of its equivalent Canadian business. Now we know why Caribbean loan margins were so fat: The outsized returns reflected higher risk. In finance, after all, there is no free lunch.

Escalating lending woes

What started as a corporate lending problem has morphed into a mortgage-market meltdown. Consumer credit is also suffering. Just before Christmas, RBC took another $50-million charge related to its Caribbean residential mortgage book, while CIBC has warned that further FirstCaribbean writedowns could come.

Before the crisis, foreigners piled into Barbados, buying up properties on the island’s west coast. The boom was so fierce that a luxury mall—Limegrove Lifestyle Centre—was built, attracting tenants such as Cartier and Louis Vuitton. Developments like the Port Ferdinand luxury marina, which can house 120 vessels up to 18 metres long each, also sprung up. Today, however, both are surrounded by properties with “For Sale” signs. The situation is eerily similar in the Bahamas, where it would take more than a decade to unload all the foreclosed properties at the average annual rate of home sales.

Much of this mess dates back to practices put in place years ago—in some cases, before the Canadian banks made their Caribbean acquisitions. “The credit adjudication of RBTT left a lot to be desired,” says Richard Young, the former head of Scotiabank Trinidad, who retired in 2012. “I used to compete with them, so I knew the type of stuff they were doing.” If, for example, a client had a good relationship with a branch manager, he or she could simply call up and get extra credit, regardless of their banking profile. “The customers loved it.”

FirstCaribbean, meanwhile, was happy to lend during a property boom. There was a belief in Barbados that real estate prices would go up by 10% a year. Believing the hype was bad enough, but once the bubble popped, CIBC was left holding bad loans tied to houses and land.

Although each bank now has its own restructuring plan, the common denominator is the need to lower costs. Since revenues aren’t growing, savings have to come from slashing expenses. That’s easier said than done. RBC, for example, operates in 18 countries and territories in the region. It is governed by 17 regulators and deals in eight currencies. Negotiating layoffs and centralizing back-office functions is a nightmare.

To make matters worse, the Caribbean is an inefficient market. In Trinidad, people joke about waiting years to receive a tax refund. Roads are so bad that getting around a capital like Port of Spain takes a major chunk out of the workday.

Such inefficiencies have crept into the banking sector. Mobile banking barely exists in the Caribbean. RBC’s branch—or banking hall, in local lingo—in Port of Spain’s Independence Square is one of the bank’s biggest in the world; it has to be, because West Indians would rather wait in line than pay electronically. The effect on costs is brutal. A recent study of Trinidadian banks found that total operating costs averaged about 6% of total assets; the figure in the European Union was just 2%.

Trinidad isn’t alone. Until Scotiabank opened a new branch in Montego Bay, Jamaica, last fall, the lineup at its existing branch demonstrated that Jamaicans will wait an hour or more to deposit a cheque.

The Canadian way of doing business is also at odds with Caribbean culture. Terrence Farrell is fluent in both worlds. A native Trinidadian who served as deputy governor of the country’s central bank, he completed his PhD at the University of Toronto. Many West Indians, he says, will claim “God is a Trini” or “God is a Bajan”—the slang names for Trinidadians and Barbadians. The meaning: “We are fortunate; things will always work out for the best.” In Farrell’s view, too many people think, “we don’t need to make any effort, we don’t need to plan, to harness our resources, to work hard.”

West Indians also have incredible national pride. Canadians may view the Caribbean as one coherent region, but each island likes to take digs at the other, and in many cases they really don’t trust one another. “Bajans operate on two speeds,” according to a Trinidadian saying. “Slow, and slower.”

A lack of economic diversity

Such cultural assumptions are, of course, debatable. But bank investors can’t ignore the hard facts of the Caribbean’s underlying economic woes; nor can they ignore a changing regulatory landscape.

For tourism, the Canadian, U.S. and U.K. economies finally look promising—maybe. “The truth is, you can get sun, sea and sand anywhere nowadays,” warns Pamela Coke Hamilton, an American-educated lawyer who heads the Caribbean Export Development Agency, based in Barbados. It kills her to say it, because she was raised in Jamaica, but the Caribbean is one of the most expensive sun destinations to visit, and a recent IMF study found the region’s share of global tourism is falling.

Another major problem, Coke Hamilton says, is that the islands mostly offer the same thing, so they simply take tourists from one another. Today the Cayman Islands is a hot destination, siphoning off high-end tourists from Barbados and Bahamas. A few years from now, Cuba could be the sexy spot—especially if U.S. developers pile in. Coke Hamilton argues that each country must develop a unique strategy. Health City Cayman Islands, for instance, opened in 2014, designed to lure North Americans looking to shorten surgery wait times, for a price.

On the regulatory front, a recent crackdown on tax evasion, particularly by U.S. lawmakers, has forced banks to abide by new rules. In 2010, the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act became law, holding financial institutions to much tougher reporting standards for offshore assets. Barbados and the Cayman Islands had been well known as tax havens, giving Westerners good reason to do business and to own properties there. Globally, regulators are also getting tougher on money laundering—which is done, among other channels, through offshore accounts in the Caribbean—and that’s made banks think twice.

As for the energy market, prices aren’t expected to rebound any time soon—which means Trinidad is in trouble. In January, American and British energy explorers were still chatting over rum punches in Port of Spain’s hotel bars, but that could quickly change. The country’s lack of economic diversity has a price. “In Canada, you’ll have a hit in certain provinces, but [the country] can absorb it a little easier,” says Reshard Mohammed, chief financial officer of Scotiabank Trinidad. In his country, “a prolonged issue will be more problematic.”

Trinidad does have some substantial buffers—its unemployment rate is just 3.2% and its “A” sovereign debt rating is the highest in the Caribbean. But Farrell, who is a director at Trinidadian lender Republic Bank, warns that the government didn’t save much for a rainy day. Norway, he points out, started producing oil in the 1970s, and its sovereign wealth fund is now worth almost $900 billion (U.S.); Trinidad has been producing energy for 100 years, but its equivalent fund is worth just $5 billion. (Of course, Alberta’s isn’t much better, relatively speaking.)

What the future holds

Some banks are more willing to admit missteps than others. “It’s fair to say that there were some mistakes we made around leadership and the business model,” says Kirk Dudtschak, RBC’s head of Caribbean banking since 2013. When RBC bought RBTT, it had dreams of creating a pan-Caribbean bank, a strategy that entailed eliminating individual country heads in favour of a central command. It took five years before management realized they had lost the pulse of each island, and then reinstalled local leaders, starting in 2013.

While not as candid, Scotiabank has also discussed the region’s problems for some time—though chief executive Brian Porter, who once ran the lender’s international banking arm, joked at the January investor conference that no one cared until now. “The Caribbean has been under a fair degree of stress for seven years and I talked about it,” he told the audience, but “nobody really asked me any questions.”

Because there now are questions, the banks try to calm investors by stressing that the English-speaking Caribbean is on an upswing as tourism levels rebound somewhat. (Puerto Rico, by contrast, is in its eighth year of recession.) Given the region’s strong economic ties to the U.S., it also augurs well that the American economy is heating up.

The banks can also point to their cost-cutting. Scotiabank is closing branches across the Caribbean; CIBC, which declined to comment for this story because it is working on restructuring plans, has talked about tightening its operation, which is currently spread across 17 islands; and RBC recently installed a Common Caribbean Operating Model to increase efficiency, instituting charges such as a small teller fee to wean customers off in-person banking. Under these initiatives, head counts are falling at all the banks. RBC’s Caribbean work force is less than 5,000, compared to 6,500 people two years ago. “Many parts of the region are in a deep or long-term recession,” Dudtschak says. “Everything we’re doing is about repositioning our business within the current economic environment…to ensure our business is sustainable for the long term.”

The elephant in the room is whether any lenders will cut and run altogether. RBC, after all, did it once before. The Canadian giant originally owned RBTT but sold it during the 1980s when Trinidad was hit by plunging energy prices.

For now, RBC and its peers tell anyone who asks that they have no plans to leave. They say they’ve been in the region for more than a century and remain deeply committed. After a while, however, their responses sound as rehearsed as an American politician being asked about presidential ambitions.

At this point, sources say the chances of a major sale are slim because buyers are hard to come by. Global banks such as HSBC and Citibank are shrinking their footprints. Private equity players may poke around from time to time, but they often get spooked once they start digging through financials, according to a source familiar with the Canadian banks’ operations. For instance, some islands don’t keep adequate digital records (or any digital records) of their housing appraisals, so anyone trying to assess the banks’ loan portfolios must bring in armies of people to dig through file folders.

Until buyers materialize with a reasonable offer, the most likely outcome is that the banks will continue to prune. But shrinking is expensive and arduous, involving wrestling with regulators, cancelling property leases and paying severance packages, among other things.

If Canada’s banks are lucky, the U.S. economy will keep gathering steam. If not, they should find solace knowing they’ve been here before, and it eventually got better. Trinidad reeled when oil prices crashed in the 1980s; Jamaica is in a perpetual relationship with the IMF; and Barbados has long been at the whim of tourist dollars.

However, those facts haven’t quelled speculation that one of the Canadian banks could pull the plug—especially when all three have new CEOs. CIBC is considered to have the highest flight risk. Former CEO McCaughey, who doubled down in the region, retired last year, as did former COO Richard Nesbitt, who oversaw the Caribbean operation. The region is now under the watch of retail banking head David Williamson, and he already has his hands full trying to turn around CIBC’s Canadian operation.

RBC is more of an enigma. The bank is taking its restructuring seriously; that could mean that it wants to run the division long-term, or, like someone who wants to sell a house, is renovating simply in hopes of fetching a better price.

Scotiabank, meanwhile, is considered the most likely to stay. It is, after all, Canada’s most international bank, and its Caribbean operation is widely regarded as the region’s most efficient. Besides, Scotiabank has endured much worse in countries such as Argentina and Venezuela; it remains profitable in the Caribbean. For all these reasons, the place, and its tilting fortunes, may well be woven into the bank’s DNA.